West Baltimore's massive new quarter-billion dollar Uplands neighborhood just south of Edmondson Village has been in development for well over a decade now, so an initial verdict and midcourse critique for correction can now be rendered.

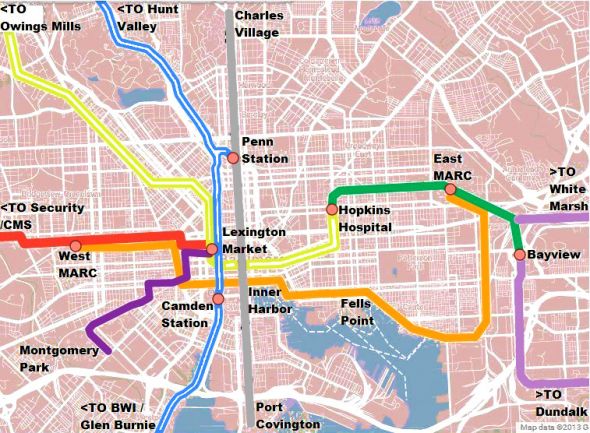

Uplands is still the best hope for the outer US 40 corridor. The Red Line's transit promises couldn't drive growth. If anything, new growth must drive the Red Line.

The Uplands community looks great for what it is. The design is very attractive. It's too bad they mowed down all the great old trees, despite giving lip service to saving them, but that's what big-time developers do, right? They bulldoze trees...

And it's too bad the housing bubble came along just when the city actually started thinking it had some semblance of a healthy real estate market. Now the city is pretty much back to its "old normal" economy - featuring wishful hype for its own sake.

This kind of large-scale development has never lived up to its hype in Baltimore. Cold Spring New Town is probably the worst example, with the worst hype-to-success ratio over the past fifty years. Uplands has at least done much better than that. But it can do better.

The verdict: Uplands has been underwhelming, both in helping grow the city and in stabilizing its surrounding communities.

Design is only a means to an end. The best example of that is Heritage Crossing, which has truly superior design but has done virtually nothing to help the surrounding communities of Upton, Lafayette Square and the "Highway to Nowhere" corridor. At least Uplands avoids making the same mistakes again.

Uplands has avoided Heritage Crossing's most obvious mistake - it blends in well with the remaining neighborhood just to the south of Old Frederick Road (see photo above). By comparison, Heritage Crossing is like an island.

But Uplands seems to be the other extreme. It blends in too well. When the original Uplands was developed around the 1940s/50s, along with Yale Heights to the south of Frederick Avenue, it represented growth of the old turn-of-the-19th-century "streetcar suburb" of Irvington. In the long run, it didn't help much there either. The city does not need new Uplands to be a mere repeat of old Uplands and Yale Heights, with trendier 21st century postmodern architecture.

Old Irvington is potentially extremely attractive, but it needs a lot of help that it's not getting. In a way, it's physically an older version of the most attractive neighborhoods north of Uplands in the Edmondson Avenue corridor - Rognel Heights, Hunting Ridge and Ten Hills. They need help too.

The Edmondson Village shopping center, once home of two anchor department stores, is not aging well, and is bringing these adjacent neighborhoods down. The newer Giant Food supermarket has helped as much as could be expected, but not enough.

Uplands' slogan is "urban convenience, suburban charm". We can all judge the convenience and charm for ourselves. But why not the other way around? Given our hype resistance, it implies that being in the city isn't charming. New Uplands needs something better.

Blending in is important, but to be a catalyst for growth which captures potential buyers' imagination, new development in Baltimore needs a strong "Wow Factor". To some extent, these are contradictory. If it blends in, it doesn't stand out. In order for Uplands to do both, it requires an orientation that can raise both the old and the new to a higher level.

Uplands can indeed do both. The key is to orient the next phase of the new Uplands to Uplands Parkway, the adjacent beautiful wooded two-lane parkway to the west, and thus also orient it to Ten Hills just beyond (see above photo) which is one of the most gorgeous neighborhoods in all of Baltimore.

Ten Hills is like the land that time forgot. That may be good when when one sees how time has ravaged much of the city, but all neighborhoods, like people, are forced to go through life cycles and must do so in a healthy sustainable way. The bigger they come, the harder they can fall.

Ten Hills isn't even oriented to adjacent, beautiful Uplands Parkway, much less to Uplands, so there are currently two degrees of separation.

Here's how to achieve the "Wow Factor" for the entire greater community: Orient the next phase of the Uplands development to Uplands Parkway. That will symbolically unify everything into one grand vision: New Uplands, old Uplands, Ten Hills and the entire Edmondson Avenue/US 40 corridor. Symbolic unification is even better than real unification, because it can mean anything that anyone wants it to mean. All things to all people. Everyone can blend in but stand out.

There is another dimension to the Uplands site's "Wow Factor": The incredible victorian mansion (photo below) vacated by New Psalmist Church when they moved out several years ago. The preservation and renovation of this treasure is a centerpiece of the Uplands master plan. However, being a centerpiece is far different from being a catalyst.

Since the mansion has already been secured to prevent further deterioration, it does not need to be a priority for Uplands' next phase of development, even though it is well-suited for institutional uses, offices, elderly housing or condos. At this time, it only needs to be displayed as a visible reminder of the potential beauty of the entire Uplands community, old and new.

In fact, orienting the Uplands development's next phase to Uplands Parkway, and toward Ten Hills, will strengthen the context of the old mansion as part of the larger community. Right now, the old mansion looks out of place. It will look much less out of place when it is seen as part of a larger context which includes Uplands Parkway and Ten Hills, the houses of which were originally inspired by the mansion.

Compare the architecture in the photo of the Uplands mansion with that of the Ten Hills houses on Nottingham Road. They blend in but stand out.

The one element to create the greatest "Wow Factor" for Uplands is an entrance view corridor from Uplands Parkway, looking upward at the mansion in the distance (as shown in the photo above). This would create a strong memorable theme to unify everything.

Since there is a small cliff near the top of the view corridor, the entrance road would probably not be able to reach the mansion at the summit. That could add to the drama, allowing the view to unfold from various other angles within the development site.

Site design is an art, as Baltimore has known from as long ago as when the Olmsteads built their famous communities in Roland Park, Northwood and Guilford. What the Olmsteads did not succeed in doing was integrating their communities with their surroundings. The most famous and notorious aspect of this was the shameful and unconstitutional way they kept blacks and Jews out using deed restrictions.

But the urban design reinforced this. Roland Park was not integrated with Hampden, which has only been rectified recently. Falls Road and the Jones Falls Expressway are still barriers. Guilford is very ungracefully walled off from Greenmount Avenue and York Road. Even the new neo-Olmsteadian Heritage Crossing is a fortress cut off from its surroundings.

The Uplands project presents a golden opportunity, with all the raw materials to do it right, to create a "Wow Factor" to elevate the entire West Baltimore corridor. Phase One has been a decent start, but more of the same in the next phase will not be good enough.

Uplands needs a strong gateway from Uplands Parkway, with a view corridor oriented to its stunning victorian mansion. And the developers can even do what they do best: Chop down the trees that block the view.

Uplands is still the best hope for the outer US 40 corridor. The Red Line's transit promises couldn't drive growth. If anything, new growth must drive the Red Line.

The Uplands community looks great for what it is. The design is very attractive. It's too bad they mowed down all the great old trees, despite giving lip service to saving them, but that's what big-time developers do, right? They bulldoze trees...

And it's too bad the housing bubble came along just when the city actually started thinking it had some semblance of a healthy real estate market. Now the city is pretty much back to its "old normal" economy - featuring wishful hype for its own sake.

This kind of large-scale development has never lived up to its hype in Baltimore. Cold Spring New Town is probably the worst example, with the worst hype-to-success ratio over the past fifty years. Uplands has at least done much better than that. But it can do better.

The verdict: Uplands has been underwhelming, both in helping grow the city and in stabilizing its surrounding communities.

Design is only a means to an end. The best example of that is Heritage Crossing, which has truly superior design but has done virtually nothing to help the surrounding communities of Upton, Lafayette Square and the "Highway to Nowhere" corridor. At least Uplands avoids making the same mistakes again.

| Old Frederick Road looking east toward Athol -.new Uplands on the left (north) and old Uplands on the right (south). |

How to blend in

Uplands has avoided Heritage Crossing's most obvious mistake - it blends in well with the remaining neighborhood just to the south of Old Frederick Road (see photo above). By comparison, Heritage Crossing is like an island.

But Uplands seems to be the other extreme. It blends in too well. When the original Uplands was developed around the 1940s/50s, along with Yale Heights to the south of Frederick Avenue, it represented growth of the old turn-of-the-19th-century "streetcar suburb" of Irvington. In the long run, it didn't help much there either. The city does not need new Uplands to be a mere repeat of old Uplands and Yale Heights, with trendier 21st century postmodern architecture.

Old Irvington is potentially extremely attractive, but it needs a lot of help that it's not getting. In a way, it's physically an older version of the most attractive neighborhoods north of Uplands in the Edmondson Avenue corridor - Rognel Heights, Hunting Ridge and Ten Hills. They need help too.

The Edmondson Village shopping center, once home of two anchor department stores, is not aging well, and is bringing these adjacent neighborhoods down. The newer Giant Food supermarket has helped as much as could be expected, but not enough.

Uplands' slogan is "urban convenience, suburban charm". We can all judge the convenience and charm for ourselves. But why not the other way around? Given our hype resistance, it implies that being in the city isn't charming. New Uplands needs something better.

| Beautiful Nottingham Road in Ten Hills, just west of Uplands Parkway. Looking closely, a small glimpse of the new Uplands development can be seen among the trees between the first two houses. |

The "Wow Factor"

Blending in is important, but to be a catalyst for growth which captures potential buyers' imagination, new development in Baltimore needs a strong "Wow Factor". To some extent, these are contradictory. If it blends in, it doesn't stand out. In order for Uplands to do both, it requires an orientation that can raise both the old and the new to a higher level.

Uplands can indeed do both. The key is to orient the next phase of the new Uplands to Uplands Parkway, the adjacent beautiful wooded two-lane parkway to the west, and thus also orient it to Ten Hills just beyond (see above photo) which is one of the most gorgeous neighborhoods in all of Baltimore.

Ten Hills is like the land that time forgot. That may be good when when one sees how time has ravaged much of the city, but all neighborhoods, like people, are forced to go through life cycles and must do so in a healthy sustainable way. The bigger they come, the harder they can fall.

Ten Hills isn't even oriented to adjacent, beautiful Uplands Parkway, much less to Uplands, so there are currently two degrees of separation.

| Narrow, bucolic Uplands Parkway seen from the wooded St. Bartholomew's Churchyard, with the new Uplands neighborhood in the background and its vacant huge future-phase lot in between. |

Here's how to achieve the "Wow Factor" for the entire greater community: Orient the next phase of the Uplands development to Uplands Parkway. That will symbolically unify everything into one grand vision: New Uplands, old Uplands, Ten Hills and the entire Edmondson Avenue/US 40 corridor. Symbolic unification is even better than real unification, because it can mean anything that anyone wants it to mean. All things to all people. Everyone can blend in but stand out.

There is another dimension to the Uplands site's "Wow Factor": The incredible victorian mansion (photo below) vacated by New Psalmist Church when they moved out several years ago. The preservation and renovation of this treasure is a centerpiece of the Uplands master plan. However, being a centerpiece is far different from being a catalyst.

| Uplands mansion left next to the rubble from New Psalmist Church which vacated the site. |

Since the mansion has already been secured to prevent further deterioration, it does not need to be a priority for Uplands' next phase of development, even though it is well-suited for institutional uses, offices, elderly housing or condos. At this time, it only needs to be displayed as a visible reminder of the potential beauty of the entire Uplands community, old and new.

In fact, orienting the Uplands development's next phase to Uplands Parkway, and toward Ten Hills, will strengthen the context of the old mansion as part of the larger community. Right now, the old mansion looks out of place. It will look much less out of place when it is seen as part of a larger context which includes Uplands Parkway and Ten Hills, the houses of which were originally inspired by the mansion.

Compare the architecture in the photo of the Uplands mansion with that of the Ten Hills houses on Nottingham Road. They blend in but stand out.

| Uplands mansion at the top of the hill as seen from Uplands Parkway |

What to do: Maximize the mansion

The one element to create the greatest "Wow Factor" for Uplands is an entrance view corridor from Uplands Parkway, looking upward at the mansion in the distance (as shown in the photo above). This would create a strong memorable theme to unify everything.

Since there is a small cliff near the top of the view corridor, the entrance road would probably not be able to reach the mansion at the summit. That could add to the drama, allowing the view to unfold from various other angles within the development site.

Site design is an art, as Baltimore has known from as long ago as when the Olmsteads built their famous communities in Roland Park, Northwood and Guilford. What the Olmsteads did not succeed in doing was integrating their communities with their surroundings. The most famous and notorious aspect of this was the shameful and unconstitutional way they kept blacks and Jews out using deed restrictions.

But the urban design reinforced this. Roland Park was not integrated with Hampden, which has only been rectified recently. Falls Road and the Jones Falls Expressway are still barriers. Guilford is very ungracefully walled off from Greenmount Avenue and York Road. Even the new neo-Olmsteadian Heritage Crossing is a fortress cut off from its surroundings.

The Uplands project presents a golden opportunity, with all the raw materials to do it right, to create a "Wow Factor" to elevate the entire West Baltimore corridor. Phase One has been a decent start, but more of the same in the next phase will not be good enough.

Uplands needs a strong gateway from Uplands Parkway, with a view corridor oriented to its stunning victorian mansion. And the developers can even do what they do best: Chop down the trees that block the view.