|

| "Highway to Nowhere" wall adjacent to Franklin Street houses |

Highways and the threats of highways shape everything around them. They motivate people. They move people... literally. "Stop the Road" delves into all this and the results can still be seen in Baltimore over four decades after the last highway bulldozer of 1979.

Among all the various highway proposals described in the book are some that would have prevented the Inner Harbor. Others would have prevented Fells Point, Canton or Federal Hill as we now know them. Even Mount Vernon Place and its Washington Monument rubbed up against a proposed expressway plan. But ultimately, all of these vital Baltimore areas survived and later flourished due to victories in hard fought road battles by ordinary people who loved their neighborhoods.

These victories stand in stark contrast to the lone isolated expressway segment in inner West Baltimore where the brave and tireless road warriors lost and the road planners won - Interstate 170, later dubbed the "Highway to Nowhere". Evans Paull explains this with astonishing historic background in vivid blow-by-blow detail.

|

| "Highway to Nowhere" looking east with rail transit right-of-way in the median strip |

The "Highway to Nowhere" was built because Mayor McKeldin signed its condemnation ordinance in 1967, which became a self-fulfilling prophesy of deterioration and destruction. Soon after there was virtually nothing left to save. The immediate motivation for this was "slum clearance", even though before the expressway plan, the corridor was a flourishing African-American community on what was a major part of the only small slice of the city's real estate which was open to its residents.

The large amount of up-front federal highway money that was spent for the highway's planning, engineering and demolition created another problem. A "hard and fast" deadline of June 1973 was imposed on getting construction started, constituting a threat that the federal government would demand repayment if the project was cancelled. Since William Donald Schaefer, mayor at the time, was frustrated over the lack of progress on the other segments of his expressway system, he took it out on West Baltimore and thus gave the order to proceed with the "Highway to Nowhere". Mayor Schaefer's reasoning was apparently that if he couldn't get this piece under construction, how could he ever get the rest of the system built?

Schaefer was trapped by his own hype. He promised that Baltimore's expressway system would provide a great economic lift to the city. So it's ironic that the expressway segments which were NOT built became the famous symbols for the so-called Baltimore Renaissance. Meanwhile, the "Highway to Nowhere" has produced absolutely nothing for its surrounding neighborhoods. Not a single new development of any size has occurred in the highway's Franklin-Mulberry corridor since its completion in 1979.

|

| Abandoned housing on Harlem Avenue near "Highway to Nowhere" |

After that, the next promise was to build a rail transit line in the median of the highway on land reserved for it in the design. For the first twenty years after the highway was completed, this was just another pipe dream, until 1999 when the Red Line was first proposed as part of a new regional rail transit plan.

If anything, however, the fifteen year Red Line planning effort prolonged the useless highway's life even more, since it encased the transit line. To the current day, there has still never been an official proposal to demolish the highway and return the Franklin-Mulberry corridor to its adjacent communities.

|

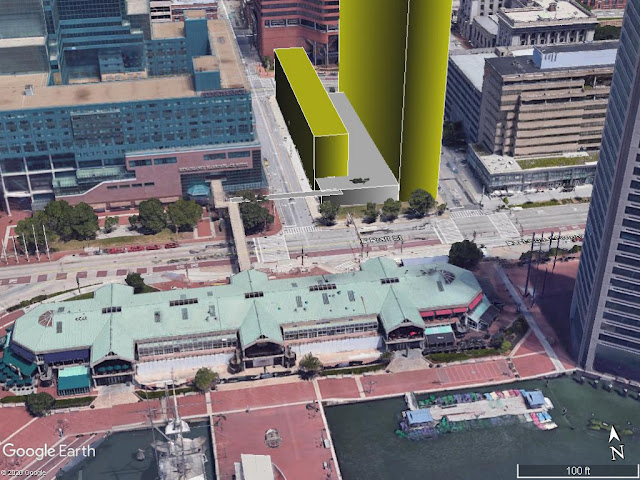

| MTA rendering of proposed Harlem Park Red line Station in median of "Highway to Nowhere" |

So even now, the "Highway to Nowhere" continues to haunt us

The 2015 cancellation of the Red Line by Governor Hogan is the last planning event of the "Highway to Nowhere" saga to be covered in Paull's book. But the Red Line cancellation had practically nothing to do with the highway. The Red Line was cancelled because about half or more of its estimated $3 billion price tag (most recently $3.8 billion) was devoted to its downtown tunnel that didn't even connect to any of the existing rail transit system. Just as with the expressway system, the Red Line as a whole was a money pit, but only crumbs were allocated to West Baltimore.

It's also interesting that even while Red Line planning was still proceeding circa 2008, the highway's original development platform cap concept was revived in the administration of Mayor Sheila Dixon. A new catchphrase was even coined: the "Highway to Somewhere". That catchphrase literally meant that the two mile highway could be made more useful if it went to "somewhere" rather than "nowhere". But the platform was as impractical in 2008 as it was four decades before when first proposed. Instead, just as during the original road war, the proposed cap seemed to be more of a ploy to try to win community support for a mega-dollar transportation project than something that made intrinsic sense.

So planning still continues to the present day. Amtrak is now building a totally new West Baltimore MARC Station at the west end of the highway as part of its new Frederick Douglass West Baltimore tunnel project to be completed in 2031. This brand new station will offer the opportunity to provide the best, fastest and most convenient rail service between Baltimore and Washington and serve as the west anchor of the corridor.

This year, the state also just completed the first phase of its latest East-West Corridor Transit Study. This brings Franklin-Mulberry transit planning full circle. One of the identified options in the current study is a heavy rail line that bears an uncanny resemblance to the 1968 plan that would spur off the existing Lexington Market Metro Station, which was completed in 1982.

But there are big differences between what we knew then and what we know now. By 2022, we have confidently demonstrated that the "Highway to Nowhere" is a failure. About a decade ago, the entire highway was closed for about six months to enable the demolition of its west retaining wall at Pulaski Street for an expansion of the MARC Station parking lot and for a future Red Line. Increased congestion did not happen in the corridor. This was easily predictable because all the traffic has always had to exit the brief highway west of Pulaski Street anyway.

We also know that transit is as important as ever to the future of the corridor, but this needs to include a mix of local, regional and inter-regional travel. Most significantly, West Baltimore needs to take advantage of its proximity to the Washington Metropolitan area as an essential future asset, including not just DC but also its suburbs with new MARC linkages to the upcoming Purple Line to New Carrollton and to the Amazon HQ2 in Northern Virginia. This is why it needs an absolutely accessible first class flagship MARC station instead of the cobbled together setup with grossly undersized platforms and no ADA access that's there now.

We also know that the Red Line as planned from 1999 to 2015 had serious flaws, and that a faster and higher capacity heavy rail line as conceived way back in the late 1960s would be a far more flexible solution. It can now be built as a spur off the existing Metro system that already extends 16 miles from Hopkins Hospital to Owings Mills and can be efficiently and affordably extended in an incremental manner by as little as two or more miles at a time, eastward to Bayview, Dundalk, Sparrows Point and White Marsh and westward to Edmondson Village and Woodlawn.

We also know that getting rid of the highway would open up far more opportunities for transit oriented development and other amenities which can be developed in no other way, particularly in a light rail line encased in a highway median strip.

We also know how to make economic growth happen without displacement of current residents, from experience elsewhere, most notably in the Station North neighborhood near Penn Station.

So the saga is not yet completed, and a new chapter of economic growth and prosperity is just beginning. The "Highway to Nowhere" somehow managed to survive the Road Wars as documented in Evans Paull's book, when the highways through all the other communities did not. But it should not survive any longer.