Sagamore Development Company's giant 13 million square foot plan calls for changing almost everything in Port Covington. But some things are more changeable than others. And since change is expensive, the plan should be selective in what is changed - to invest its precious Tax Increment Financing and other infrastructure dollars wisely.

Hanover Street is the key to integrating Port Covington and old South Baltimore. Simply making Hanover Street work should enable the whole street plan to work.

The Sagamore plan is to be commended for going to great lengths to try to enhance the linkage between South Baltimore and Port Covington. It does this by proposing to eliminate the I-95 exit ramp to Hanover, by extending Light Street southward over the railroad tracks and under I-95, and even by lowering Hanover Street itself to make it part of the new development.

But all of these things would be very difficult and expensive to do, and would probably have major extraneous effects which have not yet been revealed or discussed.

While there is no doubt that a 13 million square foot development is a very large omelet that will require breaking some big eggs, some eggs may be too tough to crack. Hanover Street is the egg that can be cracked with a fork. A fork in the road, that is.

Gigantic Port Covington will need all the access it can get from Interstate 95, and the nation's biggest highway may be the one piece of infrastructure that can't be tampered with to suit Sagamore. And in any event, the current ramp system actually works well, providing all the necessary connections in three directions - both north and south, to and from I-95, and also to and from downtown on I-395.

In fact, it's not the ramp system's connections to and from the Interstate highways that are the problem. It's the opposite ends of these ramp connections into Port Covington that are problematic. Which is actually fortunate, because Sagamore and the city have a lot more control over what happens in Port Covington than on I-95.

Moreover, the goals are not mutually exclusive: If the best possible access is provided at the least cost and disruption, Port Covington can be made a relatively seamless part of the city as a whole.

As part of its renewal, Hanover Street was closed through Otterbein, and it's traffic bent around it in a slalom to Charles and Light Street to serve downtown and the Inner Harbor. Then when I-395 and Conway Street were completed, much of the through traffic shifted away from Hanover to the expressways. That traffic reduction enabled the city to remove Hanover Street's peak period parking restrictions. It took a while for housing renewal on Hanover Street to catch up with the surrounding more local streets, but eventually its houses were rehabbed as well.

So now Hanover Street is poised to be the primary urban grid linkage between South Baltimore and Port Covington. The only problems are that Hanover Street in Port Covington is oriented far more to the I-95 ramps and to the bridge to the south toward suburban Ritchie Highway than it is to the huge future development. This results in a hostile anti-urban environment on Hanover Street, accentuated by its huge and complex intersections with McComas Street and Cromwell Boulevard, along with the ramp and "jughandle" traffic merging and diverging into the flow.

Here's the key: The intersection of Cromwell and Hanover should be modified so that Cromwell connects directly to the Hanover Street bridge to the south. In turn, the intersection of Cromwell and McComas Street should be modified to facilitate access to I-95. This was the original concept back in the 1980s, but it was deemed too expensive to modify McComas Street underneath I-95 to make the ramp connections work.

Hanover Street is the key to integrating Port Covington and old South Baltimore. Simply making Hanover Street work should enable the whole street plan to work.

The Sagamore plan is to be commended for going to great lengths to try to enhance the linkage between South Baltimore and Port Covington. It does this by proposing to eliminate the I-95 exit ramp to Hanover, by extending Light Street southward over the railroad tracks and under I-95, and even by lowering Hanover Street itself to make it part of the new development.

But all of these things would be very difficult and expensive to do, and would probably have major extraneous effects which have not yet been revealed or discussed.

While there is no doubt that a 13 million square foot development is a very large omelet that will require breaking some big eggs, some eggs may be too tough to crack. Hanover Street is the egg that can be cracked with a fork. A fork in the road, that is.

Gigantic Port Covington will need all the access it can get from Interstate 95, and the nation's biggest highway may be the one piece of infrastructure that can't be tampered with to suit Sagamore. And in any event, the current ramp system actually works well, providing all the necessary connections in three directions - both north and south, to and from I-95, and also to and from downtown on I-395.

In fact, it's not the ramp system's connections to and from the Interstate highways that are the problem. It's the opposite ends of these ramp connections into Port Covington that are problematic. Which is actually fortunate, because Sagamore and the city have a lot more control over what happens in Port Covington than on I-95.

Moreover, the goals are not mutually exclusive: If the best possible access is provided at the least cost and disruption, Port Covington can be made a relatively seamless part of the city as a whole.

Hanover Street has already been bent around Otterbein

The small but elegant Otterbein neighborhood is at the opposite north end of the South Baltimore peninsula from Port Covington, and achieved comparable objectives when Hanover Street's traffic pattern was realigned there in the late 1970s.

The Otterbein neighborhood had been condemned and slated for destruction to build Interstate 395 into downtown. But a revised plan saved it, which led to it becoming perhaps the premiere rowhouse neighborhood in all of Baltimore. It also created a site for the convention center.

As part of its renewal, Hanover Street was closed through Otterbein, and it's traffic bent around it in a slalom to Charles and Light Street to serve downtown and the Inner Harbor. Then when I-395 and Conway Street were completed, much of the through traffic shifted away from Hanover to the expressways. That traffic reduction enabled the city to remove Hanover Street's peak period parking restrictions. It took a while for housing renewal on Hanover Street to catch up with the surrounding more local streets, but eventually its houses were rehabbed as well.

So now Hanover Street is poised to be the primary urban grid linkage between South Baltimore and Port Covington. The only problems are that Hanover Street in Port Covington is oriented far more to the I-95 ramps and to the bridge to the south toward suburban Ritchie Highway than it is to the huge future development. This results in a hostile anti-urban environment on Hanover Street, accentuated by its huge and complex intersections with McComas Street and Cromwell Boulevard, along with the ramp and "jughandle" traffic merging and diverging into the flow.

All roads lead to Port Covington

Hanover Street's problems are local, so the solution should be local.

Cromwell Boulevard, built as the spine road for the first wave of Port Covington development in the 1980s (which ended up only being the Sun printing plant), is actually much better suited to handle the through traffic than Hanover Street.

In fact, Cromwell is not very well suited to be an urban street of the type Sagamore is trying to cultivate in its plan. Instead, it serves as more of an edge, adjacent to the Locke Insulator plant and the Gould Street power station, and as an access road for the development in between which will be oriented to the waterfront.

The Sagamore plan gets rid of the eastern portion of Cromwell toward McComas Street and I-95, but this seems wasteful and unnecessary.

Instead, Cromwell Boulevard should essentially replace Hanover Street as the through traffic spine between the Hanover Street Bridge and northward to I-95, Key Highway, the port and downtown.

But the much larger Sagamore development plan raises the ante, and proposes far more expensive changes than any of this.

Making the intersection of Cromwell / McComas / I-95 work this way would divert through traffic away from the intersection of Hanover / McComas / I-95, and allow that critical area to be oriented almost entirely to local and I-95 traffic only, and thus to integrating Hanover Street between Port Covington and old South Baltimore.

The Sagamore plan attempts to soften that intersection by getting rid of the I-95 off-ramp and lowering Hanover Street, which would have far more widespread impacts and be far more expensive. Instead, Hanover Street could be modified as follows:

1 - Orient the I-95 ramps directly into new Port Covington streets. Since the ramps link to Hanover on diagonals, these streets could be oriented to similar angles: The I-95 off-ramp merges with Hanover at angle which points to the southeast, so it could be oriented to a new street at a similar southeast angle proceeding in a straight shot into Port Covington.

2 - Similarly, the on-ramp onto I-95 from Hanover is oriented from the southwest, so a new street could be similarly oriented from this point to the southwest.

3 - The angles between these two streets could be used to define an entire street grid for the new development.

4 - McComas Street to the east of Hanover would become an unnecessary complication to this street grid and could be eliminated, or localized to better serve the proposed athletic facilities in the catacombs under I-95. Eliminating McComas would be particularly beneficial at Cromwell because it would eliminate the weave from the I-95 off-ramp onto Cromwell, which is currently not allowed.

5 - Similarly, existing Hanover Street to the south toward Cromwell Boulevard and the bridge over Middle Branch would also be an unnecessary complication and could be eliminated. The Sagamore plan to "lower" the street is tantamount to eliminating it anyway, so this plan would be a simpler, cleaner and more direct way to accomplish the same thing.

As Yogi Berra said: When you reach a fork in the road, take it!

The concept is simple. Hanover Street is an integral part of South Baltimore. At the south end of its urban grid near I-95, there should be a fork in the road to direct you toward the heart of either the east or west sides of Port Covington.

But all of this is conceptual and schematic, and should be tailored to specific conditions and needs. The Port Covington plan would generate a huge number of trips which would need to be accommodated. The plan's development densities should be tailored to the capacity of the system to serve each specific site.

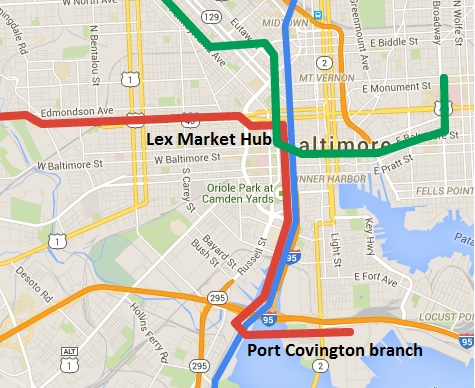

The optimum alignment of the light rail branch should also be given special attention, particularly maintaining the current Hanover Street rail underpass to keep the transit line away from traffic conflicts. There is also room for roadway and pedestrian underpasses if these would also be beneficial and reducing conflicts.

Issues relating to rehabilitating or replacing the Hanover Street Bridge over Middle Branch may also become important, but these may also present additional opportunities, both in the long term and in the interim when traffic must be diverted elsewhere anyway.

Now that Wal-Mart has been shut down, short term considerations should not be a major constraint on what can be done.

Port Covington's potential is virtually unlimited, but the traffic capacity and infrastructure budgets are not. Let's make it count.